Chapter 7: The Solomons Campaign

Introduction

Japan embarked upon her career of conquest with the intent of making herself economically self-sufficient. With the rapid expansion into the East Indies, carried out against weak and disordered opposition by the outnumbered Allies, half of her plan was realized; an area rich in the necessary vital resources had been seized, all that remained was to defend and exploit it.

To protect both this newly conquered area and the Japanese homeland, a defensive perimeter was established running from the Kuriles on the north through the Malay Archipelago and westward to Burma. In the southeast this defensive line was drawn through the Solomons with Rabaul on New Britain serving as nerve center and citadel.

In early 1942, United States carrier raids on Japanese positions in the Marshalls and the carrier-mounted B-25 raid on the homeland impressed the Japanese with the desirability of further advancing the outer defenses of their newly captured empire. In the south, the Fiji Islands, New Caledonia, Port Moresby, and Guadalcanal were selected as the key objectives. These sited dominated the vital United States-Australia-New Zealand line of communications, and their possession would contribute importantly to the defense of the Empire.

In order to check this expansion and to contain the Japanese within the already occupied area, limited countering moves were undertaken by the United States. During this phase the capture of Port Moresby by sea was prevented by an American carrier force which intercepted and turned back the Japanese invasion fleet in the Battle of the Coral Sea. The intended further expansion to the eastward was stopped shortly thereafter at the Battle of Midway and such losses in aircraft carriers inflicted on the Japanese that the advances into New Caledonia and the Fijis, which were also dependent on success in New Guinea and the Solomons, had to be abandoned. Within the Solomon Islands chain however the Japanese continued to advance with the purpose of establishing a number of strong defensive outposts for Rabaul.

Initial United States Landings

In early summer of 1942 the Japanese commenced a consolidation of positions on the eastern coast of New Guinea and on the island of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomons. Harbor and airfield construction was begun, and aviation and ground troop garrisons installed. To prevent the Japanese from gaining too strong a hold in the latter area, the United States undertook an amphibious operation in which it was planned "to occupy and defend Tulagi and adjacent positions (Guadalcanal and Florida Islands) and the Santa Cruz Islands (Ndeni) in order to deny these areas to the enemy and to provide United States bases in preparation for further offensive action." This operation was carried out by forces of the South Pacific Area, with support from Southwest Pacific forces in the form of operations aimed at interdiction of Japanese naval, air and submarine activity in the Eastern New Guinea-Bismarcks area.

On 7 August 1942 the United States counteroffensive in the Pacific was begun with the landing of the reinforced First Marine Division in the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area of the Solomon Islands. Three task forces participated in this operation, the transport and landing force with its escorting cruisers and destroyers, a carrier force giving air support at the scene of the landings, and a force of flying boats and shore-based aircraft which provided long range search and bombing. The initial landings were successfully carried out,

--105--

and on Guadalcanal a partially completed airstrip was captured, the possession of which was destined to be the object of extremely bitter fighting on land, on sea, and in the air.

Battle of Savo Island

The United States landings on Tulagi and Guadalcanal immediately provoked the Japanese into energetic countermeasures designed to dislodge the Marines from their precarious foothold. During the first and second days after the landings, the reaction was limited to air raids which attempted to disrupt the disembarkation of troops and supplies, but a greater effort was at hand; on 8 August a Japanese cruiser force was dispatched from Kavieng and Rabaul with orders to "attack and destroy enemy transports in the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area."

Five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer under the command of Rear Admiral Mikawa rendezvoused between Cape St. George and Green Island, passed north of Bougainville, through Bougainville Strait and down "the Slot" toward the transport area off Guadalcanal.

At about 1130 (zone minus 11 time) while still north of Kieta and some 300 miles from Guadalcanal, this force was sighted by an Allied search plane which maintained contact for about an hour. As a deceptive measure, Admiral Mikawa reversed course and stood back towards Rabaul, returning to his original course only when the plane had departed. Although reports of this contact were immediately sent out by the search plane, confusion occurred in the relaying of the message, and the information did not reach all ships and commands concerned with resulting lack of alertness. [The report did reach Admiral Turner, the Task Force commander at Guadalcanal, by late afternoon of the 8th.]

As just such a raid as this had been anticipated, the covering force of five United States and two Australian cruisers, with their accompanying destroyers, was divided into a northern and a southern screening force and stationed across Indispensable Strait, to the north and the south of Savo island. During the action which followed, however, only one of the Australian cruisers was present as the officer in tactical command had retired in the other cruiser to the transport area in order to attend a conference called by the Task Force Commander.

About 2 hours prior to their arrival off Savo island, the Japanese cruisers catapulted four scouting planes to reconnoiter Guadalcanal and to illuminate the transport area by dropping flares. Additional information concerning the location of the United States transports was also transmitted to the raiding force by Japanese observers on Guadalcanal who were able to observe the area by the light from a burning United States transport damaged by bombing during the afternoon.

At about 0130, while steaming in column formation with the heavy cruiser Chokai in the lead, the Japanese sighted the southern United States radar picket destroyer close aboard to starboard moving slowly south. The Japanese force was immediately slowed to 12 knots to reduce the visibility of the ships' wakes, and all guns were trained on the destroyer. As the United States ship made no move either to give battle or to escape, doubt arose in the minds of the staff on the Japanese flagship as to whether they might not have been seen and reported, but not engaged in order to be lured into an ambush. Nevertheless, they held their fire and, after safely passing astern of the United States destroyer, increased speed to 26 knots and rounded the southern coast of Savo Island.

A few minutes later the southern group of Allied cruisers was sighted off Kokumbona and within 2 minutes of the sighting all Japanese ships had fired torpedoes; by this attack, both heavy cruisers of this group, Chicago and Canberra, were damaged, the latter so severely that she had to be sunk the next morning. Immediately following this attack, the Japanese turned left towards the northern group, which had been the subject of continuous reports by Chokai's observation plane. During this turn, the Japanese column became separated into two groups, Chokai and Cruiser Division Six heading for a position to the east of the northern United States group, while Cruiser Division Eighteen and the single destroyer passed to the westward.

--106--

As the Japanese approached the northern group, they momentarily employed their searchlights to illuminate their targets and then opened fire at point blank range. Surprise was again achieved, and the United States ships replied at first only with their antiaircraft batteries and with machine guns. Subsequently a few main battery salvos were fired, one of which struck Chokai just aft the navigating bridge, damaging the searchlights and the operations room, destroying all charts, and killing about 30 men. So overwhelming was the Japanese fire, however, that the heavy cruisers Quincy and Vincennes sank within an hour, and the Astoria the next morning.

Following this eminently successful action, the Japanese ships turned northwest around Savo Island. Due to the loss of all charts on the flagship, the delay in reassembling their broken formation, and the fear of being caught at daylight within range of dive bombers from the United States carriers, of whose presence to the southward they had knowledge through radio intelligence, the Japanese retired without returning to attack the now unprotected transports. Their only loss of the operation occurred as Cruiser Division Six was entering harbor at Rabaul the next morning, when the heavy cruiser Kako was sunk by a United States submarine [S-44.]

In this disastrous battle, the Allies lost four heavy cruisers as a result of fatigue, lack of proper precautions, and confusion. Coming as it did at the very start of the Allied counteroffensive, this loss dealt a heavy blow to the then limited Allied naval strength in the Pacific, and its consequences were only gradually overcome. [In addition, Admiral Fletcher pulled the covering aircraft carrier force out following this battle, leaving the transports no choice but to withdraw -- taking with them the 7th Marine Regiment, plus large stores of ammunition and food needed by the Marines left ashore.]

--107--

Appendix 38

Battle of Savo Island, 8 August 1942

| Forces Involved |

| Allied: |

Japanese: |

| |

Southern Group: |

|

Cruiser Division Six: |

| |

|

Australia (CA) Admiral Crutchley, R.N.1

Chicago (CA) Capt. H.O. Bode, U.S.N.

Canberra (CA)

Bagley (DD)

Patterson |

|

|

Chokai (CA) (F) Admiral Mikawa, I.J.N.

Aoba (CA)

Furataka (CA)

Kinugasa (CA)

Kako (CA) |

| |

Northern Group: |

|

Cruiser Division Eighteen; |

| |

|

Vincennes (CA) Capt. F.L. Riefhohl, U.S.N.

Astoria (CA)

Quincy

Helm (DD)

Wilson (DD) |

|

|

Tenryu (CL)

Tatsuta (CL)

One destroyer |

| |

Radar Patrol: |

|

| |

|

North: Ralph Talbot (DD)

South: Blue (DD) |

|

1Absent from battle area during action. |

| Losses |

| Allied: |

Japanese: |

| |

Quincy (CA)

Vincennes (CA)

Canberra (CA)

Astoria (CA) (damaged and subsequently sunk) |

|

None |

| Damaged |

| |

Chicago (CA) (Major)

Ralph Talbot (DD) |

|

Chokai (CA) (Minor: No. 1 Turret damaged, out of action. Operation room destroyed)

Aoba (CA) (No. 1 and No. 2 twin mount torpedo tubes hit and set afire) |

--108--

Appendix 39

Battle of Savo Island

Japanese Track Chart

--109--

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

Following the Battle of Savo Island, 8-9 August 1942, the Japanese landed minor garrison reinforcements on Guadalcanal without opposition. Their offensive efforts, however, were primarily devoted to air raids and ship bombardments while sizeable reinforcements were gathered at Rabaul and in the Shortland Islands in preparation for a major assault to dislodge the tenacious Marines from Henderson Field.

On 19 August, a convoy consisting of 4 transports, escorted by 4 destroyers under the command of Admiral Tanaka, departed Rabaul to arrive at Guadalcanal on the 24th with 700 army personnel of the Ikki Detachment and 800 marines of the Yokosuka Fifth Special Landing Force. About 100 miles to the eastward of this group, 2 screening units were operating; 1 included the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, while the other included the light carrier Ryujo. In the general vicinity of the transport force the seaplane carrier Chitose operated her ship-based seaplanes. This entire force proceeded toward Guadalcanal under cover of the shore-based reconnaissance aircraft of the 25th Air Flotilla which, operating from Rabaul, searched as far as 164° east longitude.

In order to prevent this landing, two United States task forces, one centering on Saratoga, and the other on Enterprise, were operating about 100 miles southeast of the Solomons. At about 1040, 23 August, initial contact with the enemy transport force was made by long-range reconnaissance plane. The two carriers immediately attempted to close the range, and Enterprise launched an eight-plane search to a distance of 187 miles covering sectors between 345° and 045° true bearing. Although the Japanese invasion force was still beyond this scouting radius, three screening submarines were attacked with inconclusive results. At 1510, Saratoga launched an attack group composed of 31 dive bombers armed with 1,000-pound bombs and 6 torpedo carrying planes. Due to a breakdown in communications causing a delay in the receipt of a message indicating a change of course of the enemy, this striking group failed to make contact and was forced to land at Guadalcanal, where it remained overnight, returning to Saratoga the next morning. Similarly, an afternoon Marine attack group from Guadalcanal and another Enterprise search group again failed to locate the enemy, although again a submarine was attacked.

At dawn on the 24th, 20 dive bombers took off from Enterprise to search over a distance of 200 miles between true bearings of 290° and 070°, and again the only contact was with a single submarine. in the meantime another patrol plane had sighted the Ryujo group at 0935 in latitude 04°40' south, longitude 161°15' east, or 281 miles bearing 343° from the United States carriers. At 1028 and again at 1249 the Chitose reported being tracked by a United States flying boat which was driven away by three fighters, although it escaped being shot down. At 1320, in order to determine whether other carriers were in the vicinity of this contact, Enterprise was ordered to conduct an additional search while Saratoga prepared her group for a strike. At 1440 Enterprise search planes located Ryujo distant 198 miles bearing 317° from the United States carriers and at 1500 Shokaku and Zuikaku were located and unsuccessfully attacked by 2 Enterprise search planes 198 miles from their parent carrier on a bearing 347°. Communication difficulties caused by the limitation of plane equipment, which provided only one radio frequency for both fighter direction and scouting plane message, resulted in delay in receipt of these contact reports. At 1435 the Saratoga air group was launched to attack the Ryujo at its estimated position, and at 1620 this attack was delivered. Although only 4 bomb hits and one torpedo hit plus several near misses were claimed by the attacking air group, the Japanese reported that the Ryujo received 10 bomb hits from the dive-bombers, burned fiercely, and sank. Not a single United States plane or crew member was lost.

Shortly after the carrier attack upon the Ryujo, two flights consisting of three and four B-17s, respectively, of the 11th Bombardment Group operating from Espiritu Santo took off the engage the enemy.

--110--

The three-plane flight claimed four hits at about 1705 on a carrier reported to be dead in the water (Ryujo at this time was burning and sinking) while the four-plane flight claimed two an hour later on another carrier estimated to be to the eastward of the first. Photographs at the time did not substantiate these claims, nor did the Japanese report such hits.

Chitose reported that two carrier-type dive-bombers attacked her at 1815, damaging the topside equipment, rupturing the port fuel oil tanks and flooding the engine room to such an extent that a 7° list was incurred. Soon thereafter, fire broke out in the crew's quarters and among the planes, several of which were jettisoned, and Chitose retired to Rabaul.

Simultaneously with the first attack upon Ryujo, Japanese planes from Shokaku and Zuikaku attacked the Enterprise, which was launching a second wave against Ryujo. The Japanese air group was first detected upon the radar screen at a distance of 88 miles from Enterprise and was constantly tracked for a period of 22 minutes prior to the attack. However, poor radio discipline of the United States fighter pilots and the lack of an alternate communication channel prevented effective fighter direction. Several of the Japanese bombers penetrated the screen and at 1709 scored three hits on Enterprise plus several damaging near misses. Excellent damage control saved Enterprise, and retirement from the battle area was made at 24 knots. During the concluding phases of this attack, Enterprise and North Carolina were bombed by eight horizontal bombers which "approached unobserved at 15,000 feet;" the salvoes missed North Carolina by about 2,000 yards. This ended the action of the 24th, except for a bombardment of Guadalcanal about midnight by the destroyers, Isokaze, Kawakaze, and Kagero from the Eight Fleet, which were later attacked but not damaged by Marine dive-bombers from Guadalcanal.

Wasp, returning from Noumea, was joined by North Carolina and proceeded to a point southeast of Guadalcanal to reinforce the Saratoga force. However, no further carrier action occurred.

Despite the withdrawal of the supporting force during the night, the enemy transport units continued towards Guadalcanal. At dawn a group of 12 Marine dive-bombers departed Henderson Field in search of the enemy reinforcement force, locating it at 0935. In the subsequent attack, the light cruiser Jintsu sustained a bomb hit between No. 1 and No. 2 turrets which flooded the forward magazines and caused such extensive damage that Admiral Tanaka transferred his flag to the destroyer Kagero and ordered Jintsu, escorted by the destroyer Suzukaze, to Truk for repair. At the same time the 9,300-ton transport Kinryu Maru was bombed and set on fire. About 1015, while standing by this gutted and abandoned transport, the old destroyer Mitsuki sustained three hits from a flight of eight B-17s of the 11th Bombardment Group operating out of Espiritu Santo. At 1140 this destroyer sank, leaving only the destroyer Yayoi and Patrol Boats Nos. 1 and 2 to rescue the survivors of both ships. At 1200, the attempt to land troops was cancelled by order of the Commander Out South Seas Force, and all ships retired to the Shortland Islands.

Except for contacts with scattered Japanese units during their retirement, this was the last action of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the results of which prompted the commander of the Japanese Second Destroyer Squadron to write "Gradual reinforcement of landing forces by small units, subjects all of the troops involved to the danger of being destroyed piecemeal. Every effort must be made to use large units all at once." The recommended procedure was soon followed in the subsequent Battle of Santa Cruz.

--111--

Appendix 40

Battle of Eastern Solomons, 25 August 1942

| Forces Involved |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

Main Body: Third Fleet: |

| |

Shokaku (CV)

Zuikaku (CV)

6 Battleships |

| |

Advanced Force: Battleship Div 11: |

| |

Hiei (BB)

KirishimaBB) |

| |

Cruiser Division 7: |

| |

Suzuya (CA)

Kumano (CA)

Chikuma (CA) |

| |

Destroyer Squadron 10: |

| |

Nagara (CL) (F)

12 Destroyers |

| |

Detached Force: |

| |

Ryujo (CVL) |

| |

Cruiser Division 8: |

| |

Tone (CA) (F)

2 Destroyers |

| |

Occupation Force: |

| |

Jintsu (CL) (F)

Suzukaze (DD)

Umikaze (DD)

2 Destroyers

4 Transports |

| |

Ikki Detachment: |

| |

700 Army |

| |

Yokosuka 5th Special Landing Force: |

| |

800 Marines |

| |

Bombardment Force DesDiv 30: |

| |

Less: Uzuki and Mochizaki

Isokaze (DD)

Kawakaze (DD)

Kagero (DD) |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

|

|

| |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

Ryujo (CV) (By dive-bombers)

Mutsuki (ODD) (By B-17s)

Kinryu Maru () (By dive-bombers)

90 aircraft |

|

| Damaged |

| |

|

|

| Allied: |

| |

Enterprise (CV) (3 bomb hits by dive-bombers) |

|

| |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

Chitose (CVS) (2 hits by dive-bombers)

Jintsu (CL) (1 hit by dive-bombers) |

|

--113--

Appendix 41

Battlle of the Eastern Solomons: Track Chart

--114--

Battle of Cape Esperance, 11 October 1942

Following the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, the Japanese continuously reinforced their Guadalcanal garrison with personnel from the Ikki and Kawaguchi units by means of destroyer transports. At times as many as 900 troops were landed in a single night at Cape Esperance on the northwest tip of Guadalcanal by these ships which normally departed from the Shortland area and steamed southeast toward Guadalcanal, transiting the inside passage between New Georgia, Choiseul and Santa Isabel Islands so as to reach the landing area at night. Landings of this nature were generally accompanied by bombardment of the airfield by additional ships covering the landing or by the destroyer transports after debarkation was completed.

In order to stop this constant stream of reinforcement, a small United States cruiser task force sortied from Espiritu Santo on 7 October to take up station in the vicinity of Russell Island. This force was directed to "search for and destroy enemy ships and landing craft."

On 10 October, two planes from each cruiser of the force conducted a negative search of the area used by the Japanese landing reinforcements, and proceeded to Tulagi with instructions to rejoin their parent vessels at 1600 the next day. At about 1345, 11 October, United States patrol planes reported a Japanese force of cruisers and destroyers about 210 miles to the northwest enroute to Guadalcanal. The presence of this force was again confirmed at 1810 when the ships were sighted 110 miles from Guadalcanal.

The United States cruiser task force immediately proceeded towards Cape Esperance in order to be in position to intercept the Japanese about midnight. While en route, the planes which had been based at Tulagi returned to the cruisers, but due to the imminence of battle, they were not taken aboard. instead they and one additional plane from each ship were dispatched to Tulagi in order to clear the cruiser decks of aircraft in preparation for a night action.

At 2200, the remaining cruiser planes were catapulted to search for the Japanese force. The Salt Lake City plane crashed on catapulting and burned; thinking that the bright light from the flares in this plane was a signal from the beachhead, the approaching Japanese answered with their searchlights. Shortly after 2300 and again 0130, the San Francisco search plane reported one transport and two destroyers off the north beach of Guadalcanal. However, these ships were neglected in the search for the more important Japanese cruiser and destroyer force; at 0230 they were seen retiring to the northwest unharmed.

At about 2232, as the United States ships approached the passage between Savo Island and Guadalcanal, radars on both Boise and Helena picked up a formation of five ships, at a range of 18,000 yards to the northwest. This report was transmitted to the task force by voice radio, but the United States commander was unable to visualize the situation, since the flagship was not equipped with the most recent radar. At that time, he was concerned lest the ships reported as the enemy force be his own five destroyers out of position following a recent course change. Shortly thereafter, an exchange of messages indicated that these destroyers were overtaking the cruisers on the latter's right flank. This put the destroyers in the line of fire between the opposing cruiser forces.

At 2346 the Helena opened fire, followed by the Salt Lake City, Boise and Farenholt. The Japanese force was completely surprised. The heavy cruiser Aoba and the destroyer Fubuki received hits immediately and executed a turn to the right, followed by the heavy cruiser Furutaka, while the heavy cruiser Kinugasa swing left as she began firing at the United States cruisers. This maneuver removed Kinugasa from the general bearing of fire and permitted her to act almost unmolested.

Aoba, which was leading the enemy column was struck by the opening United States salvoes which killed a large number of personnel on the bridge, including Admiral Gota, the officer in tactical command. Fubuki was sunk before completing her turn. Furutaka, subjected to the concentrated fire of all United

--115--

States ships as they "capped the T", sustained such severe damage that she sank soon after reversing course. Aoba and Kinugasa fled to the northwest, while the destroyer Murakumo started to retire, then returned to the battle area and rescued a number of survivors. This delay was fatal, since both Murakumo and the destroyer Natsugumo which joined her were sunk the next morning by dive-bombers and fighters from Guadalcanal.

During the battle the United States destroyer Duncan, which had closed to attack with torpedoes, was caught in a position between the two forces and fired on by both, receiving such damage that she sank the next day. Boise and Farenholt received major damage while the Salt Lake City sustained minor damage. After turning back the Japanese force, the United States ships retired to Espiritu Santo.

--116--

Appendix 42

Battle of Cape Esperance, 12 October 1942

| Forces Involved |

| Allied: |

Japanese |

| |

San Francisco (CA)) Rear Admiral N. Scott, USN

Salt Lake City (CA)

Boise (CL)

Helena (CL)

Farenholt (DD)

Buchanan (DD)

Laffey (DD)

Duncan (DD)

McCalla (DD) |

|

Aoba (CA) Rear Admiral Goto

Furutaka (CA)

Kinugasa (CA)

Furutaka (CA)

Murakumo (DD)

[Missing from oroginal table, but mentioned in text:]

Fubuki (DD)

Natsugumo (DD) |

| Detailed Losses |

Sunk |

| |

Duncan |

|

Furutaka (CA)

Fubuki (DD)

[Missing from oroginal table, but mentioned in text:]

Murakumo (DD)

Natsugumo (DD) |

| Damaged |

| |

Boise (CL) (Major)

Salt Lake City (CA) (Minor)

Farenholt (DD) (Major) |

|

Aoba (CA) (Major)

Kinua (CA) (Minor) |

--117--

Appendix 43

Track of Japanese Forces

Battle of Cape Esperance

11 Oct 1942

--118--

Battle of Santa Cruz, 25-26 October 1942

Between August and the first part of October all attempts made by the Japanese to regain Guadalcanal had ended in failure. This was in part due to their lack of landing craft, which forced them to send reinforcements to the battle area in small units where they were destroyed piecemeal. After 2 months of occupation, the American defenses were being so rapidly developed that the Japanese decided that a major assault was necessary. They planned first to gain control of the airfield; then, while basing planes there, to mop up the remaining American units at will.

In preparation for this large-scale attack, efforts were made to sever the United States lines of communication to Guadalcanal, and Submarine Force "A", composed of the six submarines I-4, I-5, I-7, I-8, I-22 and I-176, was deployed in the Indispensable Straits. On 31 August, while patrolling in a position northwest of Espiritu Santo, the I-26 damaged the Saratoga with a torpedo hit. On 6 September, the I-11 unsuccessfully attacked Hornet in the same area. In the same vicinity of 15 September, Wasp was sunk by the I-19, and North Carolina and O'Brien were damaged. In order more fully to exploit this lucrative area, Submarine Force "B", composed of I-9, I-15, I-21, I-24, I-174, and I-175, was additionally assigned. On 20 October, while just east of San Cristobal, the heavy cruiser Chester was damaged by the I-176. On the 14th and again on the 23, the I-7 shelled Espiritu Santo in nuisance raids. Following the battle on the 26th, both "A" and "B" Forces were ordered to proceed to an area north of the Santa Cruz Islands to intercept the United States task force and destroy damaged ships. however, the Japanese submarine effort, though of limited success, did not interrupt the flow of supplies and personnel so necessary for maintaining the United States possession of Guadalcanal, and on 15 October, 4,000 troops of the Americal Division landed there. Constant Japanese air raids on Henderson Field by planes based at Rabaul and staged through intermediate fields harassed construction personnel in their efforts to improve the vital airfield and other installations on the island. Enemy destroyers landed approximately 900 troops per night until the Japanese strength on Guadalcanal reached a peak of some 26,000 Army troops and 3,000 Special Naval Landing Force troops. At the same time, additional Japanese troops and supplies were being concentrated in the Rabaul-Shortland area, and long-range reconnaissance was conducted by seaplanes based on the Kiyokawa Maru in the Shortland area.

By 11 October, the heaviest Japanese naval force assembled since the Battle of Midway sortied from Truk to provide the necessary sea and air strength for the general attack. On the 13th, the battleships Haruna and Kongo bombarded Henderson Field for a period of 1 hour and 20 minutes; of the United States planes at the field, only one escaped undamaged. In an attempt to maintain this neutralization, additional bombardments were conducted by Japanese cruisers and destroyers during the next few days. Although all available planes were flown in from Espiritu Santo, so effective were the Japanese bombardments and air raids on 26 October only 23 fighters, 16 dive-bombers and one torpedo plane were available for the defense of Guadalcanal, and the operation of even this handful was limited by a critical shortage of fuel. For over a week, while the tempo of Japanese attacks was increasing, the only fuel available for the defending fighters was flown in by Marine C-47s assisted by available planes from the Army Air Force 13th Troop Carrier Squadron. Although constantly harassed in the air by fighters, and on the ground by enemy mortar fire, each plane was able to fly in enough fuel to maintain 12 fighters in the air for 1 hour. The importance of this unusual mission can be measured by the fact that on the 24th, 21 Grumman fighters were able to shoot down 20 Zeros and 1 bomber in 1 short flight.

During the period of preparation for a general assault, the Japanese estimated that 6 days would be required to properly distribute their forces following the landing of the final contingent of special troops. This landing occurred on 15 October 1942 and Y-Day was initially set as the 21st. However, during this

--119--

period, probing attacks into the American lines along the Matanikau River were repeatedly beaten back, delaying Y-Day until the 23d. On the 22d, the light carrier Hiyo developed engine trouble, the flag of Carrier Division Two was shifted to the Junyo, and returned to Truk. Early that day, 4 heavy land attacks against the Fifth marines were repulsed with the loss of over 2,000 Japanese troops and 12 tanks. Again, Y-Day was postponed until the 24th. After another series of failures to break the lines, it was postponed until the 25th, at which time Vice Admiral Nagumo, in command of the Japanese naval forces, sent a dispatch to the Island Commander calling his attention to the fact that the supporting fleet would be forced to retire due to lack of fuel if the attack was not carried out immediately.

Following receipt of this message, another and equally disastrous effort was made to break the American lines. This assault on Lung Ridge against the weary marines who had been subjected to incessant attack by land, sea, and air, carried the Japanese to the southern edge of Henderson Field, where they were driven back by a desperate counterattack. However, this measure of success prompted the Army commander to send a dispatch to the anxious naval force that the field had been captured at 2300. According to plan, 14 fighters and a few bombers from the carriers were sent to the field at dawn the next morning where they circled, awaiting a signal to land. This erroneous message was not corrected until 0700, at which time it was too late; eight United States fighters were extricated from the mud, took off, and shot down all of the Japanese planes.

During the afternoon, planes from Guadalcanal attacked a small Japanese transport force of cruisers and destroyers, inflicting sufficient damage on the destroyer Akikaze to flood one boiler room and render one engine room inoperative. This force had landed supplies and personnel and was assisting the land action with gun fire. Later during the afternoon, this unit reported that they had been again attacked, this time by six B-17s, but that no damage was sustained.

To oppose the Japanese movement at sea, two United States task forces, formed around Enterprise and Hornet, had been directed to skirt the northern shores of Santa Cruz Islands, move southwestward to a point east of San Cristobal Island and there await a chance to intercept any enemy approach to Guadalcanal. These forces, as well as the convoys proceeding to Guadalcanal were under constant surveillance between 13 and 26 October by Japanese submarines and by aircraft from the 25th Air Flotilla operating from Rabaul and the Shortland Islands.

During the night of 25-26 October, incomplete contact reports received by the United States commander indicated that the enemy was divided into two or more units. At dawn of the 26th, Enterprise launched 16 planes to search to the northwest to a distance of 200 miles. Shortly afterwards, information was received that a patrol plane had made contact with the Zuiho approximately 2 hours before. However, no attack group was launched until the information was amplified by the carrier scouts. During this search. contact was made at 0717 26 October with the Japanese Battleship Striking Force and at 0750 with the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku of the Carrier Striking Force. Two search planes completing a leg in the adjacent northern sector hastened to attack the carriers which had just been reported, but instead located and attacked the light carrier Zuiho at 0840, making two bomb hits which caused fires and such extensive damage to the flight deck as to render it inoperative.

--120--

At 0830, following these contact reports, Hornet launched an attack group composed of 15 dive-bombers, 6 torpedo planes and 8 fighters, followed at 0900 by an Enterprise wave of 3 dive-bombers, 8 torpedo planes and 8 fighters. At 0915 the second Hornet wave of 25 planes was launched. As these groups proceeded to the target independently, the flights extended over a distance of several miles, resulting in a weak defense against enemy fighter attacks. While en route to the target, the Japanese air striking groups were passed and were reported as being on their way to attack the United States carrier forces.

About 1040 the first Hornet wave fought their way through the Japanese fighter defense and arrived over Carrier Division 1, and at once attacked the flagship Shokaku, scoring four 1,000-pound bomb hits on the port side and two near the after elevator. Immediately thereafter, the Enterprise group, depleted by enemy fighter action, unsuccessfully attacked the battleship Kongo with both torpedoes and bombs. The second Hornet wave failed to find the enemy carrier groups but succeeded in locating and attacking the heavy cruiser Chikuma which was separated from the main body of the Battleship Striking Group. In this attack, two hits were made, one of which damaged the bridge while the other bomb pierced the hull and exploded in the engineering spaces, killing the crew and reducing the speed of the ship; additionally, two near misses on the starboard side inflicted severe casualties, and caused underwater damage to the hull. Chikuma was later subjected to glide and horizontal bombing attacks, but no additional damage was inflicted.

At the same time that Shokaku was being attacked, aircraft from that vessel and from Zuikaku carried out an attack on the Hornet, obtaining hits with four bombs and two torpedoes; in addition to these hits, Hornet was also crashed by two Japanese planes, one of which was piloted by the Dive Bombing Squadron Commander. Throughout the day, sporadic attacks by aircraft of Carrier Division 1, operating from the undamaged Zuikaku, continued against the Hornet; these scored one bomb and one torpedo hit and at about 1650, Hornet received a final bomb from a high-level horizontal bomber. Between 1220 and 1245 an attack by Junyo planes obtained two bomb hits on Enterprise and one each on the battleship South Dakota and the light cruiser San Juan, while a Japanese plane crashed the destroyer Smith, starting heavy fires. In addition to the damage which the United States ships received from the air, the destroyer Porter was sunk by torpedoes from the submarine I-21 while rescuing pilots who had landed in the water. At 1840 Hornet was abandoned and sunk by United States destroyers, while the United States task forces retired to Espiritu Santo. Following this action, the Japanese striking force turned southeast to close the damaged United States forces. Although they sighted the burning Hornet and the United States destroyers firing into her, no contact was made with the main United States force and the destroyers retired before the Japanese could close. At about midnight, the Japanese turned and withdrew to the north.

--121--

Appendix 44

Battle of Santa Cruz, 25-26 October 1942

| Forces Involved |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

Advance Force: |

| |

CruDiv 4: |

| |

|

|

Atago (CA) Vice Admiral Nagumo

Takao (CA)

Maya (CA) |

| |

CruDiv 5: |

| |

Myoko (CA) Flagship |

| |

CarDiv 2: |

| |

Junyo (CC) |

| |

DesRon 2: |

| |

Isuzu (CL)

2 destroyers |

| |

DesDiv 24: |

| |

4 destroyers |

| |

BatDiv 3: |

| |

Kongo (BB) Vice Admiral Kurita

Haruna (BB) |

| |

DesDiv 15: |

| |

3 destroyers |

| |

DesDiv 2: |

| |

4 destroyers |

| |

Carrier Striking Force: |

| |

CarDiv 1: |

| |

Shokaku (CV) Vice Admiral Kondo

Zuikaku (CV)

Zuiho (CVL)

Kumano (CA) |

| |

DesDiv 4: |

| |

2 destroyers |

| |

DesDiv 16: |

| |

4 destroyers |

| |

DesDiv 61: |

| |

Terutsuki (DD) |

| |

Battleship Striking Force: |

| |

BatDiv 11: |

| |

Hiei (BB) Rear Admiral Abe

Kirishima (BB) |

| |

CruDiv 8: |

| |

Tone (CA) (F)

Chikuma (CA) |

| |

CruDiv 7: |

| |

Suzuya (CA) (F) |

| |

DesRon 10: |

| |

Nagara (DD) (F) |

| |

DesDiv 10: |

| |

3 destroyers |

| |

DesDiv 10: |

| |

4 destroyes |

| |

Supply Group--Oilers: |

| |

4 transports (oil tankers)

1 destroyer

3 transports (cargo vessels) |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

Hornet (CV) (Aircraft)

Porter (DD) (Submarine)

20 planes (shot down)

54 planes (operationally)

74 total (lost) |

|

|

| Damaged |

| Enterprise (2 bomb hits, several damaging near misses) |

| South Dakota (1 bomb hit No. 1 turret; some damage to guns of No. 2 turret) |

| San Juan (1 bomb hit) |

| Smith (Japanese plane hit No. 1 gun mount) |

|

| Shokaku (flight deck damaged; maximum speed 21 knots) |

| Zuiho (flight deck damaged) |

| Chikuma (3 bomb hits on main battery control post and torpedo tubes abaft bridge; heavy damage forward; port enigne out of commission) |

| Terutsuki (DD) (medium damage) |

| Akikaze (DD) (1 bomb rendered starboard engine inoperative and flooded No. 1 boiler room) |

|

--123--

Appendix 45

Track of Japanese Forces

Battle of Santa Cruz

25-26 Oct 1942

--124--

Battle of Guadalcanal, 12-15 November 1942

The difficulty experienced by the destroyer transports used to reinforce the Japanese on Guadalcanal, in loading and unloading tanks and heavy artillery, precluded the delivery of such weapons via the "Tokyo Express." This deficiency greatly contributed to the failure of the Japanese to overcome the stubborn American resistance during the latter part of October 1942. To rectify this situation, a convoy of 12 heavy transports was assembled in the Buin-Faisi area during the first part of November, and loaded with approximately 10,000 replacement troops of the Hiroshima Division, 3,500 Special Naval Landing Force troops, heavy field artillery, and other supplies. At the same time, major surface units rendezvoused at Rabaul and Truk preparatory to supporting the vital landing. Due to the damage inflicted upon the aircraft carriers and the heavy loss of planes and pilots in the Battle of Santa Cruz 3 weeks before, no fleet air support was available and the Japanese were forced to rely upon the protection of a limited number of shore-based fighters operating over an increasing distance as the convoy approached its destination.

Initial operations on 11 and 12 November consisted of heavy raids by bombing and torpedo planes on United States transports which were unloading supplies off Lunga Point. Although practically all attacking aircraft were shot down by defending fighters and ships' guns, they succeeded in inflicting damage upon three transports, the cruiser San Francisco, and the destroyer Buchanan before being driven off. nevertheless, 90 percent of the United States personnel had been disembarked together with a large portion of supplies before the operations were finally interrupted by the approach of the Japanese heavy bombardment group.

Early on the morning of the 12th, search aircraft located Japanese forces approaching Guadalcanal from the north. One group consisted of the battleships Hiei and Kirishima in column, screened by a light cruiser and 15 destroyers; the second, more distant, group consisted of the slower transports. Although greatly inferior in gun power, the defending United States cruisers departed Lunga Channel late in the day and proceeded towards Savo island in an attempt to turn back the Japanese and to prevent them from effecting the landing and bombardment. At 0124 on the 13th, the first radar contact was made at 27,000 yards by the cruiser Helena, which immediately transmitted the information to the flagship; as the United States officer in tactical command was again embarked in the San Francisco, with inadequate search radar, he was faced with the same difficulty in assessing the situation as had been the case in the Battle of Cape Esperance a month before. Soon thereafter, other ships equipped with the latest radar installations began to broadcast enemy contacts. Before the tactical situation was clear to the United States commander, his leading destroyers were within torpedo range, and the flagship within 2,000-3,000 yards of the enemy vessels. While maneuvering to fire torpedoes and to avoid collisions, the United States force became scattered and disorganized; with each ship operating independently, the problem of identification became critical, and United States ships occasionally fired into each other.

At 0148 the Japanese illuminated the defending cruisers and fired torpedoes. Fortunately, the Japanese ships were supplied with only bombardment ammunition, but their torpedoes inflicted fatal damage upon several United States destroyers and cruisers. In the ensuing melee, the battleship Hiei was selected as the principal target, received 85 hits and fell out of control, while the destroyers Akatsuki and Yudachi were sunk. Left behind after the other ships had retired, Hiei was repeatedly bombed and torpedoed the next day by planes from Guadalcanal, and was finally scuttled and sunk by her own crew. United States ship losses were large in this furious 34-minutes night cruiser action, but the landing of supplies and bombardment of the airfield was frustrated.

Following this battle, the Japanese transport force and the remaining bombardment vessels retired during the 13th. During this retirement, small destroyer formations were located and attacked by long-range search planes with but limited success, and on the evening of the 13th, a fast cruiser force led by the Chokai

--125--

approached Guadalcanal. So seriously had the defending United States cruiser force been damaged that it retired towards Espiritu Santo, leaving the defense of the Guadalcanal area to the motor torpedo boats based at Tulagi. At 0220 on the 14th, the Japanese cruisers commenced bombarding Henderson Field. These ships were subjected to three attacks by the motor torpedo boats and finally retired at 0340 to the south of New Georgia Island. At daylight, Enterprise, which had been rapidly approaching from the south, launched a search which located the enemy cruisers. About 0800, a Marine air group from Henderson Field made a dive-bombing and torpedo attack followed immediately by the Enterprise scouting planes and air striking group. These attacks caused the sinking of the heavy cruiser Kinugasa and serious damage to the heavy cruiser Chokai, the light cruiser Isuzu, and the destroyer Michishio. Following its attack, the Enterprise air group proceeded to Guadalcanal to operate from there in further action against the oncoming transports.

At 0830 on the 14th, search planes from Southwest Pacific forces located the enemy transport force, which had been standing by north off New Georgia, and reported that it was again headed for Guadalcanal. Shortly thereafter, two Enterprise planes on search mission attacked and damaged two of these ships. To permit Enterprise to retire beyond the range of enemy aircraft during this critical period, her striking group had landed at Guadalcanal, but lack of personnel and adequate servicing equipment limited the number of air attacks which could be launched against the enemy transports from that base. In most instances it was necessary to roll bombs across the muddy field to the waiting planes, then lift and load them by hand. About 1300, a group of about 40 Marine aircraft, followed at 1500 by the Enterprise air group, attacked the approaching transports, inflicting severe damage; 8 were either sunk or gutted by fire and rendered unnavigable, while the remaining 4, after being seriously damaged, were beached near Tassafaronga, where unloading operations were attempted despite attacks by planes from Guadalcanal and B-17s from Espiritu Santo.

In support of the transport landing, the remaining elements of the Japanese heavy bombardment group, which had been turned back in the cruiser action of the 13th, again approached Guadalcanal. In the meantime, the battleships Washington and South Dakota had been detached from the Enterprise task force and had arrived in the vicinity of Guadalcanal to intercept this group and such cargo ships and transports as had survived the days' air attacks.

At midnight Washington made radar contact with the Japanese force to the northwest. At 0016, 15 November, she opened fire at 18,500 yards and immediately thereafter, South Dakota and destroyers took up the action. Opening fire in their turn, the Japanese concentrated on the United States destroyers until about 0100, when the destroyer Ayanami illuminated South Dakota, which was immediately taken under fire by the battleship Kirishima; as Washington was not under fire by the Japanese, she was left free to engage Kirishima. Abut 9 16-inch and forty 5-inch hits were made on Kirishima, resulting in such damage that she became unnavigable, and as attempts to steer by the use of the engines failed, the captain ordered the ship scuttled. The destroyer Ayanami, while using her searchlight to illuminate South Dakota, was sunk by that ship.

Although the United States destroyer losses to heavily charged warheads of enemy torpedoes were again greater than similar losses of the Japanese, this determined attack upon Guadalcanal was turned back and the Japanese abandoned all efforts to recapture that strategic island.

--126--

Appendix 46

Battle of Guadalcanal

Cruiser Night Action, 13 November 1942

| Forces Involved |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

BatDiv 11: |

| |

|

Hiei (BB) (FF) Vice Admiral Abe

Kirishima (BB) |

| |

DesRon 10: |

| |

Nagara(CL) (F) |

| |

DesDiv 16: |

| |

Amatsukaze (DD)

Tokitsukaze (DD)

Hatsukaze (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 61: |

| |

Terutsuki (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 6: |

| |

Akatsuki (DD)

Inazuma (DD)

Ikazuchi (DD) |

| |

DesRon 4: |

| |

Asagumo (DD) (F) |

| |

DesDiv 2: |

| |

Murasame (DD)

Samidare (DD)

Yudachi (DD)

Harusame (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 27: |

| |

Shigure (DD)

Shiratsuya (DD)

Yugure (DD) |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

| |

Atlanta (CLAA)

Juneau (CLAA)

Helena (CL) (torpedoed and sunk during retirmement)

Barton (DD)

Cushing (DD)

Laffey (DD)

Monssen (DD) |

|

| |

Hiei (BB)

Akatsuki (DD)

Yudachi (DD) |

|

| Damaged |

| |

Portland (CA)

San Francisco (CA)

Aaron Ward (DD)

O'Bannon (DD)

Sterrett (DD) |

|

| |

Ikazuchi (DD) (No. 1 and No. 2 guns damaged)

Murasame (DD) (No. 1 boiler room damaged)

Amatsukaze (DD) (Minor)

Hatsukaze (DD) |

|

--127--

Battle of Guadalcanal

Cruiser Night Action, 14 November 1942

| Forces Involved |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

Bombardment Unit: |

| |

|

Kinugasa (CA)

Isuzu (CL)

CruDiv 7: Suzuya (CA)

CruDiv 4: Maya (CA)

CruDiv 18: Tenryu (CV)

DesDiv 10:

Maragumo (DD)

Yugumo (DD)

Kazagumo (DD)

DesDiv 8: Michishio |

| |

Transport Unit: |

| |

DesRoon 2: Hayashio (F) Rear Admiral R. Tanaka

DesDiv 15:

Oyashio (F)

Kuroshio

Kagero

DesDiv 24:

Umikaze (F)

Kawakaze

Suzukaze

Yukikaze

DesDiv 31:

Takanami (F)

Makinami

Naganami

DesDiv 30:

Mochizuki

Amagiri |

| |

Transport Unit: |

| |

Arizona Maru

Brisbane Maru

Kumagawa Maru

Kinugawa Maru

Sado Maru

Kirokawa Maru

Nagara Maru

Yamaura Maru

Nako Maru

Yamatsuki Maru

Canberra Maru |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

|

|

| |

Kinugasa (CA)

Arizona Maru

Kumagawa Maru

Sado Maru

Canberra Maru

nagara Maru

Brisbaneru |

|

| Damaged |

|

|

| |

Kinugawa Maru

Hiorkawa Maru

Yamaura Maru

Yamatsuki Maru (all beached)

Maya (CA)

Isuzu (CL)

Yukikaze (DD)

Chokai (CA)

Michishio (DD) |

|

--128--

Battle of Guadalcanal

Nigth Battleships Action, 15 November 1942

| Forces Involved |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

CruDiv 4: |

| |

|

Atago (CA) Vice Admiral N. Kondo

Takao (CA) |

| |

BatDiv 11: |

| |

Kirishima (BB) |

| |

DesRon 10: |

| |

Nagara (CL) |

| |

DesDiv 61: |

| |

Terutsuki (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 11: |

| |

Shirayuki (DD)

Hatsuzuki (DD) |

| |

DesRonn 4: |

| |

Asagumo (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 2: |

| |

Samidare (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 6: |

| |

Ikazuchi (DD) |

| |

DesRon 3: |

| |

Sendai (CL) |

| |

DesDiv 19: |

| |

Uranami (DD)

Shikinami (DD)

Ayanami (DD) |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

| |

Benham (DD)

Preston (DD)

Walke (DD) |

|

| |

kirishima (BB)

Ayanami (DD) |

|

| Damaged |

| |

South Dakota (BB)

Gwin (DD) |

|

|

--129--

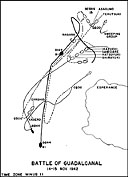

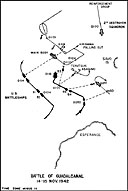

Appendix 47-1

Battle of Guadalcanal

12-113 Nov 1942

Plan of Bombardment

--130--

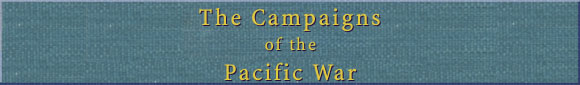

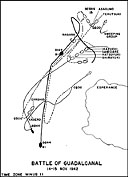

Appendix 47-2

Battle of Guadalcanal

12-13 November 1942

Japanese Track Chart

--131--

Appendix 47-3

Battle of Guadalcanal

13 November 1942

Track of Hiei and Kirishima

--132--

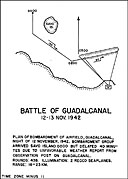

Appendix 47-4

Battle of Guadalcanal

13 November 1942

Track of Yudachi

--133--

Appendix 47-5

Battle of Guadalcanal

13 November 1942

Track Chart

--134--

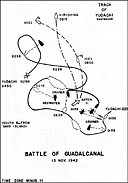

Appendix 47-6

Battle of Guadalcanal

14-15 Nov 1942

Track Chart

--135--

Appendix 47-7

Battle of Guadalcanal

14-15 Nov 1942

Track Chart

--136--

Appendix 47-8

Battle of Guadalcanal

14-15 Nov 1942

Track Chart

--137--

Appendix 47-9

Battle of Guadalcanal

14 Nov 1942

Movements of CruDiv 7

--138--

Battle of Tassafaronga, 30 November 1942

Following the Battle of Guadalcanal, 12-15 November, all plans to recapture that island were abandoned by the Japanese, and all their efforts were directed instead toward making its final capture by the Americans as expensive as possible. For a period of approximately 3 weeks, only air raids and the appearance of minor naval vessels broke the lull for United States forces. However, towards the end of November, Japanese shipping in the Shortland area increased as supplies were loaded upon fast transports, and it became apparent that a Japanese move in force to supply their hard pressed island garrison was imminent.

In order to deny the Japanese the much needed food, ammunition and technical personnel, a United States task force of five cruisers and four destroyers was formed on 27 November to intercept the rejuvenated "Tokyo Express" before it could effect a landing. At about 2300 on 29 November, this task force got underway from Espiritu Santo to intercept the Japanese landing which was expected to take place at Tassafaronga.

During the night of 29 November, Japanese Destroyer Squadron Two, consisting of eight destroyers under the command of Admiral R. Tanaka, departed Buin, passed east through Bougainville Strait past Roncodor Reef, then south to Ramos Island, then west and south around Savo Island to Tassafaronga. As darkness fell, the United States task force, approaching from the south, passed through Lunga Channel and, after being joined by two more destroyers entered Indispensable Strait. During the approach no information was available to the United States task force commander concerning the location or composition of the Japanese force other than the fact that air reconnaissance on the 29th and 30th indicated that vessels had left Buin during the night on a southeasterly course.

In order to gain information of the enemy during the approach, as well as to provide flare illumination during the battle, cruisers planes were flown to Tulagi during the afternoon of the 30th with instructions to commence search operations at 2200. Unfortunately, weather conditions delayed these operations. Shortly after 2300 Minneapolis established radar contact with the enemy force. At 2316, Fletcher launched torpedoes at a range of 7,000 yards, while at the same moment the Japanese formation slowed from 15 to 12 knots as they approached the shore line between Cape Esperance and Tassafaronga. Just as the Japanese destroyer Naganami sighted two torpedoes crossing her bow, the United States cruisers opened fire; the Japanese had no previous knowledge of their presence.

In order to guard against divulging the number and position of the destroyer force, Admiral Tanaka had ordered that gunfire be withheld until absolutely necessary for defense. Only the destroyer Takanami, serving as a picket ship on the port beam of Naganami, and hence closes to the United States cruisers, disobeyed these instructions and returned the fire, with the consequence that she was soon sunk by the overwhelming volume of fire from the United States task force.

As soon as the cruisers were sighted, all three Japanese destroyer divisions fired torpedoes, executed a simultaneous turn to the left, and retired at 24 knots without using their guns. This maneuver, which had been practiced at night for a period of a year and a half, resulted in sinking the Northampton and inflicting major damage upon the New Orleans, Minneapolis and Pensacola with the loss of only Takanami. The attempt at reinforcement of the Japanese ground troops with vital supplies was frustrated.

In discussing the operations of his well trained unit after overcoming the surprise attack of the superior United States forces, the Japanese commander was prompted to write:

The enemy had discovered our plans and movements, had put planes in the air beforehand for purposes of illumination, had got into formation for an artillery engagement, and cleverly gained the advantage of prior neutralization fire. But his fire was inaccurate, shells improperly set for deflection were especially numerous, and it is conjectured that either his marksmanship is not remarkable or else the illumination for his start shells was not sufficiently effective.

--139--

Appendix 38

Battle of Tassafaronga, 30 November 1942

| Forces Involved | |

|

|

| Japanese: |

| |

DesDiv 30: |

| |

|

Naganami (DD) (FF) Admiral Tanaka

Makanami (DD)

Takanami (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 15: |

| |

Oyashio (DD)

Kurashio (DD)

Kagero (DD) |

| |

DesDiv 24: |

| |

Kawakaze (DD)

Suzukaze (DD) |

|

| Detailed Losses |

| Sunk |

|

|

|

| Damaged |

| |

Minneapolis (CA) (Major)

New Orleans (CA) (Major)

Pensacola (CA) (Major) |

|

|

--140--

Appendix 49

Track Chart

Battle of Tassafaronga

--141--

Table of Contents **

Previous Chapter *

Next Chapter