The Solomons -- Guadalcanal

REASONS FOR THE SOLOMONS OFFENSIVE

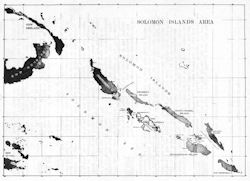

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, in January 1942, the Japanese established bases in New Britain and in the northern Solomons, In April Tulagi,, in the southern Solomons, was occupied. Our victory in the Coral Sea in May did not prevent the steady enemy advance toward New Zealand and Australia, by which our lines of communication were being increasingly menaced. As our fleet, damaged at Pearl Harbor, was gradually repaired, reinforcements were being consolidated in the Southwest Pacific, and in April it was decided to halt the Japanese advance by an attack on the Solomons. The two objectives were to be the small islands just off Florida Island known as Tulagi and Gavutu, where governmental and plantation headquarters had provided modern buildings and equipment. Later in July when our planes observed a landing field being built by the Japanese on nearby Guadalcanal Island from which land-based planes could threaten New Hebrides and New Caledonia, the occupation of that island also became imperative.

NECESSITY FOR HASTE

Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley became commander of all the United Nations' land, sea, and air forces in the South Pacific area, with the exception of New Zealand land defense forces. Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift was to lead the occupation forces as commander of the First Marine Division, the first echelon of which reached New Zealand June 14, 1942. With our success off Midway early in June, preparations were accelerated, and D-day was set for August 7th. On July 21st, the enemy landed at Ambasi and at Buna in a movement down the east coast of New Guinea paralleling that in the Solomons. The series of land-plane bases at Rabaul, Kieta on Bougainville, and on Guadalcanal, together with the seaplane bases at Gavutu, Gizo, Rekata Bay, Kieta and Buka Passage exposed our convoys bound for Australia to torpedo or bombing attack. The enemy was reported already to have 1,850 men in the Tulagi area and 5,275 on Guadalcanal. Quick action was necessary before he became too strong to dislodge without great difficulty. Large enemy ships, especially carriers, had not been observed in southern Solomon waters since the Midway and Coral Sea battles. Altogether it seemed necessary to strike at once.

THREE TASK FORCES ORGANIZED

The area west of the 159th meridian, which just touched the westernmost shores of Guadalcanal was placed under General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area. He was to interdict enemy activities west of the theatre of operations with submarines and planes. The South Pacific forces under Admiral Ghormley would occupy Tulagi and environs and also seize the Santa Cruz Islands to the east to keep them out of enemy hands. Three major Task Forces were provided for this purpose. One, Task Force NEGAT, was to supply aircraft carrier

--1--

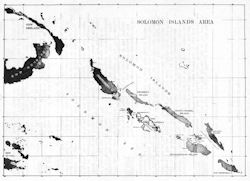

SOLOMONS ISLANDS AREA

--2--

support for the attack. The second or Amphibious Force, Task Force TARE, was to make the principal attack, transporting and landing the Marines and defending the transport convoys from surface attack. The third, MIKE, was for aerial scouting and advance bombing of the operations area. Among the transports in the Amphibious Force was the transport Hunter Liggett under Commander Louis f. Perkins, USCG, Coastguardsmen also manned the transport Alhena and other Naval vessels.1

TASK FORCES ASSEMBLE

Transports that were loaded at Wellington, New Zealand, had one combat team to each of the 12 transports, including all equipment and supplies needed to put the team ashore and keep it in action for 30 days. For every combat group, consisting of three teams, there was loaded a cargo ship with supplies for the three teams for an additional 30 days. The combined force of transports and cargo ships, including the Hunter Liggett, with escorts, departed Wellington on July 22nd. On July 1st, Group Three of the Carrier Task Force left San Diego. This consisted of the carrier Wasp and her escorts convoying five transports, including the Alhena, with the Second Marines on board. Group One of the Carrier Task Force with the carrier Saratoga, left Pearl Harbor on July 7th, and Group Two with carrier Enterprise and the battleship North Carolina, a few days later. After a rendezvous at sea, the entire force of some 80 ships proceeded to Koro Island in the Fijiis, where rehearsal exercises were held.

PRELIMINARY AIR OPERATIONS

The air attack on Tulagi and Guadalcanal began a week before the arrival of our ships. Shore based Navy and Army planes at Efate, Noumea, Tongatabu, the Fijiis and Samoa were divided into seven Task Groups. Group One was to search sectors 400 miles northwest of central New Caledonia and conduct anti-submarine patrols. Group Two was to maintain daily search of the southern Solomons and their western waters and attack enemy objectives. Group Three was to search sectors south and east of the Solomons, Group Four was to search a sector north and east of Guadalcanal from Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands. Group Five was to proceed three days before the attack to the east coast of Malaita and search a sector to the northeast. Group Six was to provide inshore anti-submarine patrol in the vicinity of Segond Channel, Espiritu Santo and operate with Group Seven, which was to provide all possible service to bombers based at Espiritu Santo and also defend the New Hebrides. In addition the three carriers Saratoga, Enterprise and Wasp were to supply air offensive and defense to the Amphibious and Landing Forces. They also obtained excellent photographs of objectives in the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area from which large scale mosaic maps were prepared.

--3--

U.S. COAST GUARD MANNED COMBAT TRANSPORT Hunter Liggett (AP-27)

--4--

ORGANIZATION OF THE MARINES

It was planned to use about 19,546 Marines who were organized into eight groups. Combat Group A was to land on Beach RED, about half way between Lunga and Koli points on the north coast of Guadalcanal, at H-hour and seize the beachhead. Combat Group B, landing in the same place 50 minutes later, was to pass through the right of Group A and seize the grassy knoll 4 miles south off Lunga Point. The Tulagi Group, landing on Beach BLUE, on the southwest coast of Tulagi at H-hour was to seize the northwest section of the island. The Gavutu Group was to land on the east coast of Gavutu Island at H plus four hours, seize that island and press on to adjacent Tanambogo. The Support Group, with the command post afloat in the Coast Guard manned Hunter Liggett, was to go ashore at Beach RED, Guadalcanal, provide artillery support for the attack, and coordinate anti-aircraft and close-in ground defense of the beachhead area. Division Reserve Group was to be prepared to land Combat Team B on Gavutu Island and attach Combat Team C to the Tulagi Group. The Florida Group was to land on Florida Island near Haleta at H-hour plus 20 minutes and seize that village. The Third Defense Battalion was to be prepared to land detachments on Beach RED and on Tulagi and Gavutu on receipt of orders. Sufficient men were to be left on board to insure expeditious unloading of all ships, working on a 24 hour basis. Shore Party Commanders were to control traffic in beach areas, calling on troop commanders in their immediate vicinity for assistance in handling supplies from landing beaches to dumps.

THE APPROACH TO GUADALCANAL

The Amphibious Task Force TARE left the Fijiis on July 31st, with Task Force NEGAT maintaining a parallel course a few miles to the north to provide reconnaissance and patrols. Task Force TARS was in circular formation with the 19 transports and cargo ships in five columns in the center, the Hunter Liggett acting as guide. On August 3rd the fleet passed through the southern New Hebrides proceeding northwest until the 159th meridian was reached on August 5th. It then headed almost due north to Guadalcanal. Meanwhile, air attacks were being made almost daily on the target area and these continued through August 6th. On that day an overcast sky and mist fortunately made enemy reconnaissance impossible. At 1615 Squadron YOKE, destined for Tulagi took the lead with Squadron XRAY, bound for Guadalcanal, 6 miles astern. At 0133 on August 7th the dark shore line of Guadalcanal could be plainly seen under the thin crescent of the waning moon. A little later Savo Island was visible. At 0300 the two Squadrons separated, Squadron YOKE passing north of Savo Island toward Tulagi and Squadron XRAY passing east to south of Savo Island along the north shore of Guadalcanal. There was no challenge and our arrival was apparently undetected. At 0530 the first planes took off from the carriers. The 15 transports of Squadron XRAY steamed along the silent Guadalcanal shore in two columns of 7 and 8 ships, arranged in the initial debarkation order. At 0613 the bombardment of the coast was begun by the Quincy and our dive bombers shortly afterwards began attacking enemy shore positions. At 0647 our transports halted 9000 yards off Beach RED.

--5--

COAST GUARD-MANNED LANDING BARGES ARE LOWERED AWAY AS DAWN BREAKS OVER GUADALCANAL

--6--

Boats were hoisted out and lowered and debarkation began. Cruisers and destroyers which were not giving fire support for the landings, formed a double arc about them as protection against both planes and submarines.

AMPHIBIOUS LANDING

The following brief description of an amphibious landing seems appropriate at this point. The combat-loaded transports and cargo ships (APA's and AKA's) arrive in the Transport Areas, which are as closely convenient to the landing beaches as depth of water and possible enemy fire will permit, and in water as smooth as possible. The ships remain under way in general ready to maneuver in case of any form of attack. Their AA batteries are kept manned; combat air patrol (CAP) for their protection is maintained by the carriers, and anti-submarine patrol is provided by planes, destroyers and other suitable craft. The transport boats, mainly the square-ended, flat-bottomed LCVP's with ramps, holding 36 men, and the larger LCM(3)'s, carrying 120 men or 60,000 pounds of cargo are put in the water and the troops are embarked. Where depth of water will permit these boats run close in to the beaches and lower their ramps in only a few inches of water. But where coral reefs or shallow water extend out so far that troops must wade or swim a considerable distance it is preferable to land as many of the earlier waves as possible in the Amphibious Tractors,2 which can run through the water, across the reefs, up the beaches and on inland if necessary.

TIMING OF LANDING

The boats or amphibious vehicles, carrying the various Regimental or Battalion Combat Teams which are to make the landing and capture the objective, proceed to the Line of Departure (an arbitrary line, located just outside of gunnery fire from the beaches) and form up in successive waves, under the direction of a Control officer and his assistants. On signal from the Control Officer, the first wave of boats or amphibious vehicles leaves the Line of Departure and heads for the Landing Beaches, their departure being so calculated that they will strike the beaches exactly at H-hour. The bombardment support, whether from aircraft, ships or artillery on shore, has been concentrating on the Landing Beaches and their immediate vicinity with maximum intensity. This is ceased or lifted inland ahead of the troops just as the first wave of troops disembarks on the beaches and deploys. Other waves follow at intervals of 3 to 5 minutes and their first endeavor is to secure a beachhead, which means sufficient area along the beaches and inland from them so that the attacking troops can deploy and maneuver, and the boat traffic can land and unload, without being under fire. As the beachheads are extended and the enemy driven back, sections of beach with fewer obstacles or with more favorable under-water gradients may be found, and the boats beached there for unloading. As the troops advance inland they receive continued support by air, naval, and land-artillery bombardment. To facilitate this Shore Fire Control Parties are landed and maintain liaison between the advancing troops and the ship, planes, and batteries.

--7--

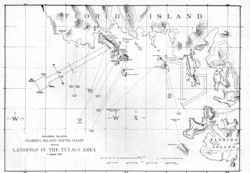

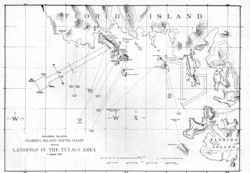

LANDINGS IN THE TULAGI AREA

--8--

COAST GUARD MANS THE LANDING CRAFT

The bombardment of the Tulagi area began almost at the same time as that of Beach RED on Guadalcanal. Going into action at 0614 our fighters and dive bombers started fires and destroyed 18 enemy planes on the water, straffing the beaches and pounding every building that might be hiding the enemy. Our ships arrived in the Tulagi transport area at 0637, half an hour behind schedule, and the landing force was immediately ordered ashore. H-hour, scheduled at 0800, remained unchanged so that none of the transports stood idle before landing their troops. Even the preliminary landing force for Haleta, and the one for Halavo some distance away, both of which were in the President Jackson, were able to make the first landing on time. Most of the landing boats had a crew of three Coastguardsmen. Coastguardsman Daniel J. Tarr was coxswain of a landing barge which put the Marines ashore in this area. Although under withering enemy fire he was able to land his boatload of Marines without the loss of a man. He then made several more trips to the shell-raked beach, carrying ammunition and supplies. Tarr was on board a Destroyer Transport which was transporting the First Raider Battalion of the Marines. At 1100 on the 8th there was an air raid by forty Japanese planes. They were intercepted by American fighters and only twenty managed to reach the transports. All but one of these were knocked down, two of the nineteen being credited to his vessel. Tarr was later awarded the Silver Star Medal for "conspicuous gallantry."

HALETA AND BEACH BLUE LANDINGS

The landing east of Haleta was made to prevent the enemy from using a promontory jutting south from Florida Island to enfilade our boats during the landing on Tulagi Island's Beach BLUE. At 0706 the landing craft left the Jackson, covered by a bombardment from the San Juan, the Buchanan and the Monssen. As the Marines approached the beach, the fire was lifted and they went ashore at 0740 without opposition. Fire support was then provided for the principal landing on Beach BLUE. This beach was completely surrounded by coral reefs. The landing boats had to halt at the edge of the reef and the men had to wade ashore. Because of this the Japanese had not expected any landing here and it was very lightly fortified. With the three naval vessels furnishing close fire support until 0755, our boats hit the reef at exactly 0800, and the Marines waded ashore without opposition. The shells from the San Juan, however, had failed to dislodge the Japanese who were still dug in on Hill 208, located in the center of Tulagi's southwest coast, and two companies advancing along the south shore were held up by heavy machine gun fire from the hill. Another company entered the jungle and. headed directly across the island. By 1012 all the waves had reached the beach.

HALAVO AND GAVUTU

The landing at Halavo, on Florida Island near Gavutu, was scheduled for 0830. Marines left the transport Jackson in landing craft promptly but were late in arriving at the Line of Departure 7 miles away. At a little before 0800 a battery on Gavutu opened fire on them at 4,000 yards. Fire support was provided by three naval vessels who were firing at the beach line at Gavutu and at a battery on the hill.

--9--

NIGHT DISPOTION OF SCREENING FORCE

--10--

By 0845 the Marines landed at Halavo and were soon ready to give fire support to our troops who were to land on Gavutu at 1200. At 1026 the first Gavutu wave left the Heywood and started the 7 mile run to the Line of Departure. Two other wave3 followed at five minute intervals. The small boats encountered choppy seas, drenching all erson.:el and equipment and making many Marines seasick. Shelling by the San Juan and bombing and straffing by planes failed to dislodge the enemy from his dugouts near the beach and on the hill. To avoid coral shoals, the landing was made on the northeastern side of Gavutu near the causeway connecting it with Tanambogo. The Japanese let them land, but many of our men wore cut down by heavy fire as they crossed the beach. The second and third waves were similarly hit ana one out of every ten men became a casualty. Hills honeycombed with dugout fortresses, both on Gavutu and Tanambogo commanded the beach and were manned with Japanese armed with machine guns, rifles, and automatic rifles. Their fire held up our men landing to the right of the beach for almost two hours, while those on the left advanced slowly.

THE GUADALCANAL LANDING

Expecting to encounter the greater resistance on Guadalcanal we had concentrated most of our landing forces there. This was one reason for the comparative ease with which the initial landing was made. Another was that the enemy could and did retire to the hills on Guadalcanal while on the small islands of Tulagi and Gavutu he was trapped and fought almost to the last man, refusing to surrender. Zero hour had been set for 0910 for the Guadalcanal landing and fire support began soon after 0900 lasting for 9 minutes. At 0913 the first troops landed without opposition on Beach RED between Lunga and Koli Points. Occupation of the Guadalcanal shore front proceeded expeditiously despite interruptions caused by enemy air attacks and about 11,000 Marines went ashore during the day. Supplies piled up faster than they could be moved away. A Coast Guard Beachmaster and about forty Coastguardsmen went on the beach to supervise the landing of the boats, their unloading, repair, and salvage when they became damaged or stranded.

ENEMY AIR ATTACKS

At 1320 on August 7th some 20 to 25 high level, twin engine bombers came in over Savo Island at 10,000 to 14,000 feet. Their attack was centered on the transports off Guadalcanal. Three were knocked down by our screening ships and transports and the rest, after attempting a pattern bombing at 10,000 feet with very poor marksmanship, disappeared behind Guadalcanal's mountains without hitting any of our ships. An hour later, 7 to 10 single engined dive bombers from the direction of Tulagi suddenly dived on Squadron XRAY off Guadalcanal, hitting the MUGFORD, with considerable damage. Fighters from the three carriers engaged enemy planes throughout the afternoon of the 7th.

LAND FIGHTING TOUGH ON TULAGI AND GAVUTU

The Raiders had occupied the western area of Tulagi with no opposition but the going was exceedingly rough on the eastern end. Here the enemy was sheltered from the bombardment in long-tunneled limestone caves in the cliffs from which they emerged to attack the Marines from machine

--11--

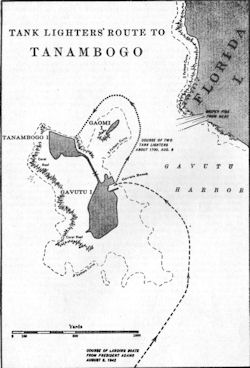

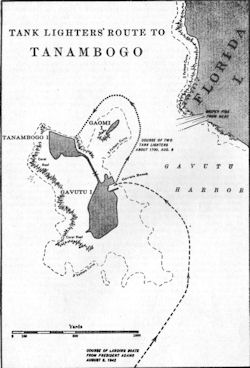

TANK LIGHTERS' ROUTE TO TANAMBOGO/

--12--

gun nests and sniping posts in the trees. At Hill 208 our men were delayed for an hour with only one platoon able to advance along the southern shore to the eastern tip of the island. By nightfall a company on the north side of the ridge was about parallel with our forces on the south. During the night the enemy concentrated on the steep slopes of Hill 281, sortied and counter-attacked, but ultimately was halted. On Gavutu our men were greatly hampered, in driving the Japanese from the dugouts and tunnels in Kill 148, by machine gun fire from adjacent Tanambogo. During the afternoon Tanambogo was heavily bombed by our planes and shelled by our destroyers, so that by 1800 we had control of Gavutu. We were unable, however, to advance across the causeway to take Tanambogo. An attempted landing on the northeastern shore to take the Japanese in the rear under cover of darkness, was defeated by an exploding gasoline tank on shore which brightly illuminated the scene. On Guadalcanal Combat Group A had reached the mouth of the Tenaru 2 miles west of Beach RED by nightfall. No contact had yet been made with the enemy anywhere bn Guadalcanal.

ENEMY RENEWS AIR ATTACK

When word was received at 1038 on the 8th that 40 enemy twin engine bombers were passing over Bougainville and proceeding southeast, all ships were ordered out of the transport areas to assume cruising disposition.

When the planes appeared at noon all ships were maneuvering at top speed. The planes approached around southeast Florida Island at about 50 feet above the water making for Guadalcanal. Our snips at Tulagi opened an intense anti-aircraft fire as the planes passed them and nine to fifteen planes were knocked down. Zero fighters were engaging carrier planes at high altitudes. While the transport formation was being turned away from the approaching planes, the screening vessels opened fire and downed several planes. When the transports added their anti-aircraft fire, the enemy formation began to break up. Many glided into the sea in flames and others crashed headlong. Only three passed entirely through and around the transports, and two of these were shot down by screening vessels to the westward. One falling plane crashed the deck of the George F. Elliott setting her afire. The destroyer JARVIS was torpedoed but still able to operate under her own power. Coast Guardsman Orviss T. O'Neal recounts this experience: "I was running between my ship, the transport Elliott, and the beach. On one trip, I had just taken a load of gasoline aboard and was moving away from the ship when the air raid alarm sounded. A few minutes later I watched as a flaming Jap plane crashed into the Elliott setting it afire. I hate to think what might have happened to my landing boat if it had ever come within reach of those flames." The fire in the Elliott spread despite all efforts to check it and. she was finally ordered sunk. Four torpedoes were fired at close range but the vessel was still afloat and on fire the following evening.

TULAGI AND TANAMBOGO SECURED

Two more battalions of Marines were landed on Tulagi about 0700 on the 8th and ordered to clear the island of Japanese, one operating in the western end and the other in the eastern. An advance over the top of Hill 281 to the southwest side of the island gave the Marines

--13--

COAST GUARDSMAN DIRECTS TRAFFIC AS LANDING CRAFT, MANNED BY COAST GUARD CREWS BRING IN STREAMS OF SUPPLIES TO THE AMERICAN BASE OF GUADALCANAL

--14--

mortar and machine-gun positions on three sides of the enemy concentration and at 1500 occupation of the island was complete. Only 3 of the 500 Japanese surrendered. The Marines had 90 casualties of whom 3 officers and 33 men were killed. Meanwhile, the Buchanan and Monssen had been shelling Gavutu and Tanambogo and at 1600 the Buchanan stood into Gavutu Harbor and opened fire on Tanambogo hill at 1100 yards. Then standing toward Gaomi, a nearby island, she shifted her fire to the southeast side of Tanambogo. About 1700 a Tank Lighter with one tank and a detachment of Marines left Gavutu for Tanambogo and landed after having met with some casualties. A second trip brought more Marines. A second Tank Lighter landed another tank which became caught on a stump and all except one of its crew were killed. A company of Combat Team C followed the two tanks ashore, half of it pushing up the southern slope of Tanambogo hill, the rest working to the east and north sides along the shore. Then a platoon of paratroops crossed the causeway from Gavutu to the south side of the island. By 2200 both Gavutu and Tanambogo were completely secured except for a few isolated nests of snipers. Of the 1,000 Japanese on Gavutu and Tanambogo all were killed except 20 captured and 70 who escaped to Florida Island. Our casualties were 158, with 5 officers and 67 men killed.

AIRDROME OCCUPIED ON GUADALCANAL

By 1500 on the 8th Combat Team A on Guadalcanal had crossed the Lunga River and entered the village of Kukum, with only light enemy fire from low knolls near the village. Combat Group B had taken possession of the airdrome by 1600 with all installations and a 3600 foot runway, encountering only one small enemy patrol. Camp sites at the airdrome had evidently been hastily abandoned, with arms and personal equipment left behind in large quantities and with no effort at demolition.

CARRIERS, TRANSPORTS AND CARGO SHIPS RETIRE

Late on the night of the 8th the aircraft carriers Wasp, Saratoga, and Enterprise and their escort's began retiring to the South, as their fuel was running low and their fighter strength had been reduced from 99 to 78 planes. It was decided to move out all the transports and cargo ships at 0600 the next day. A warning had been received that two Japanese destroyers, three cruisers and two gunboats had been sighted at 1127 on the 8th just north of Bougainville. This force was encountered that night in the Battle of Savo Island.

"DID THEY GET OFF?"

After the first landings on Guadalcanal many Coast Guard manned transports included in the first landings made numerous trips from their bases to the Guadalcanal area carrying reinforcements and supplies. They were under constant sea and air attack and the waters were heavily infested with enemy submarines. Guadalcanal was not entirely freed of Japanese until 8 February, 1943. It was while evacuating a detachment of Marines from a point where enemy opposition had developed beyond anticipated dimensions that Douglas A. Munro, a signalman first class, of the U.S. Coast Guard died heroically on September 27, 1942. Munro had been in charge of the original detachment of ten boats that landed the Marines

--15--

A COAST GUARD-MANNED ASSAULT TRANSPORT UNLOADS AMERICAN MARINES

--16--

at the scene. He had gotten them ashore and headed his boats back. On his return he was advised by the officer in charge that, due to unanticipated conditions, it was necessary to evacuate the men immediately. Munro volunteered for the job and brought the boats inshore under heavy enemy fire and proceeded to evacuate the men on the beach. Realizing that the last man would be in greatest danger, he placed himself and his boats in position to serve as cover. He was fatally wounded and remained conscious long enough to say only four words "Did they get off?" He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. His citation read in part "By his outstanding leadership, expert planning and dauntless devotion to duty, he and his courageous comrades undoubtedly saved the lives of many who otherwise would have perished."

COAST GUARD JOINS IN FIGHTING

The Coast Guard did not confine itself to operating boats, according to Coast Guardsman James D. Fox. When the going was tough and relief was not in sight while the Japs were putting on the pressure, the Coast Guardsmen dug their own machine gun nests which they set up in defensive spots. Others joined artillery men manning guns and still others pitched in with the infantry. One day Boatswain's Mate John Lydon volunteered for the perilous job of taking a detail of Marines to the Japanese occupied Russell Islands, sixty miles away, in an open landing boat. He completed his mission successfully and returned to Guadalcanal. Ten days later he again volunteered for the same journey. En route he heard the motors of another boat. It was dark and he cut his motor completely. The Americans remained silent as a much larger Japanese boat passed them by. Then Lydon started his motor and completed his mission. On another occasion the Japanese artillery fire became so heavy that Coast Guardsmen had to evacuate their advance point. They evacuated seventeen of their landing boats before the Japanese became aware of the maneuver and redirected their fire on the remaining boats. Two Coast Guardsmen remained there for five days repairing the shell damaged boats and then evacuated them with the aid of reinforcements. As soon as their supplies arrived they returned to the base and pushed the Japanese back farther than ever.

THE Hunter Liggett AT GUADALCANAL

Before daybreak of August 7, 1942, the transports of Task Force 62 approaching Guadalcanal divided into two units, one of which passed to the northwest of Savo Island to take position for the assault on the Tulagi-Gavutu-Florida area. The Liggett headed the other unit of transports, which passed to the south of Savo Island for the landing of Marines on the north coast of Guadalcanal. The Liggett's troops were composed of support, special weapons and headquarters groups, none of which were to be landed in the assault waves. The greater part of her boats, therefore, were dispatched to other vessels for the first trip. At 1323 about twenty Japanese bombers flying from 12,000 to 15,000 feet dropped bombs but there were no hits. Air raids continued intermittently while unloading continued, until 2200 when the beach became

--17--

FOUR-YEAR-OLD RICHARD DEXTER SON OF COMMANDER DWIGHT H. DEXTER, U.S. COAST GUARD STUDIES WITH PUZZLED INTEREST THE NEW SILVER STAR HIS FATHER IS WEARING

--18--

so clogged that unloading of the Liggett ceased, the ship remaining off Guadalcanal overnight. On the 8th at 1054 the Liggett and the rest of the unit got under way in anticipation of an air attack which came at 1204.

FOUR JAPANESE BOMBERS SHOT DOWN

Seventeen Mitsubishi heavy bombers swept over the rear screen in an apparent torpedo attack and dropped to less than 100 feet in altitude before reaching the transports. Three of the bombers passed to starboard of the Liggett below the level of the bridge at a distance of about 75 yards. Two of these were shot down by the starboard batteries, while two were downed by the port batteries. None of these Japanese planes escaped, for those which the transports missed or crippled were shot down by the forward screen. The Liggett suffered no casualties to either personnel or equipment. During the afternoon Lt. Comdr. D.H. Dexter, USCG, was detached to set up the naval establishment on Guadalcanal.

SURVIVORS TAKEN ABOARD

In the evening the commanding officer of the USS George P. Elliott came aboard the Liggett with 22 officers and 308 enlisted survivors. In the noon attack a crippled Japanese bomber had crashed upon her deck and set her afire. Soon afterward the Elliott had sunk. The Liggett continued to discharge cargo while drifting off the north coast of Guadalcanal. At 0145 on August 9 heavy gunfire was heard off Savo Island where the savage battle of Savo Island was raging. Enemy flares, dropped from a great height silhouetted the transports as though a full moon were shining. The transports sounded general quarters and got under way, maneuvering in the vicinity of Guadalcanal. Secured from general quarters at 0350 they returned to the transport area. Twice more they stood out in cruising disposition to maneuver in open water off Guadalcanal] because of reports that enemy aircraft were approaching. Shortly before noon on August 9 orders were received to hoist all boats and prepare to get under way. Many survivors and casualties of the USS Vincennes, USS Astoria and USS Quincy, three of the cruisers sunk during the engagement off Savo Island, were taken on board. The Liggett, acting as guide of Transport Group XRAY of Task Force 62, put to sea at 1510 and set course for Noumea, New Caledonia.

LIGGETT BRINGS REINFORCEMENTS TO GUADALCANAL

On October 22, 1942, the Hunter Liggett, in company with the USS Barnett and USS President Hayes left Tangatabu for Pago Pago, Samoa, where she took aboard 69 officers and 1,458 enlisted troops of Marine Combat Team No. 3. Proceeding to Vala Harbor, Efate Island, New Hebrides the troops were put thru landing exercises and on the 31st the three transports departed for Guadalcanal. After retreating southward, due to the activity of Japanese warships and planes, the convoy again headed for Guadalcanal arriving there on November 4, 1942. There she unloaded off Lunga Point. The ships had to move out of range once from Japanese shores batteries, and that night they got under way and maneuvered throughout the night. Next morning they got under way and headed for Espiritu Santo as enemy planes arrived to bombard Henderson

--19--

COAST GUARD SALVAGES SUB NEAR GUADALCANAL

--20--

Field. In the struggle to win Guadalcanal during the remainder of 1942, the Liggett carried troops and cargo to support the Marines fighting to hold the island. Many times she transferred her officers and men and boats for duty on Guadalcanal with the Naval Advance Base. She brought casualties south to hospitals and carried troops and Navy personnel south to rest and recreation centers. She transported Japanese prisoners and fueled destroyers in the forward area. On December 3 and 4, 1942, after fueling five destroyers at Guadalcanal, she took aboard 16 officers and 191 men from one cruiser and 79 casualties from five other naval vessels that had just engaged the enemy.

ENEMY SUBS ARE PRINCIPAL THREAT

Japanese submarines were the principal threat to the

Liggett and other ships at Guadalcanal at this time. Arriving at

Guadalcanal again on the 13th of December the Liggett took on board 1,635 troops

and officers of the First Marine Division and left for Brisbane, Australia. On

January 4, 1943 the Liggett again arrived safely at Guadalcanal carrying 60 officers and 1,419 enlisted Army and Marine Corps personnel and their cargo.

Submarine contacts during the trip had been numerous. This time she took back 17

officers and 744 men of the 6th Naval Construction Battalion to Auckland, New

Zealand. There were also 27planters and missionaries evacuated by the

submarine USS Nautilus from Bougainville. On February 7, 1943 the Liggett again arrived at Guadalcanal this time with 2,085 troops and passengers aboard. On the way, because of the danger from enemy submarines, the convoy had turned back to Espiritu Santo and waited there for three days. Taking aboard 109 men of the destroyer DeHaven, sunk in recent naval action, she started for Espiritu Santo, but was ordered to return to Guadalcanal which she approached on February 9th for the first time during daylight. Units of the 8th Marines were embarked for Wellington, New Zealand where she arrived safely on the 16th, after taking a longer course through the New Hebrides because of enemy submarine activity. On February 28th the Liggett again arrived safely at Guadalcanal and taking on board personnel and equipment of the 104th Infantry got under way for Suva, Fiji

Islands. Here she took on other troops and cargo for Espiritu Santo. On March

28she left for Lautoka, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands, and took on 115 officers and 1,520 enlisted men for Guadalcanal, Arriving on April 6th, she was almost unloaded and was under way for the night, when 6 high-flying Japanese bombers, just out of range of a continuous barrage of anti-aircraft fire, dropped bombs on Henderson Field.

JAPANESE AIR RAIDS

Next morning, while the USS Chevalier, was taking on fuel alongside, Japanese planes were detected approaching. So quickly did the Chevalier cast off that she left an officer and 2 men aboard the Liggett, And so swiftly did the Transport Division and its escorts get under way that the Liggett left behind 23 boats and 61 members of her crew. Although the Japanese on Guadalcanal were said to be defeated and the island secured on February 8, 1943, this Japanese air strike on April 7, 1943 was

--21--

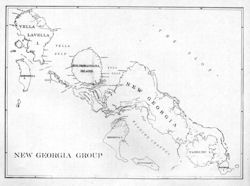

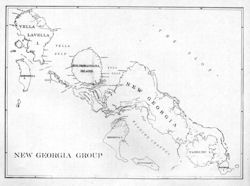

NEW GEORGIA GROUP

--22--

a big one. In an effort to halt the American advance north through the Solomons, over 100 planes had been sent to attack the ships present at Guadalcanal. No enemy planes came near the Transport Division, which had gotten away barely in time, but bombs were seen dropping 4 to 5 miles astern of the Liggett on a formation of ships, several of which were hit and sunk. On April 16 the Liggett arrived at Wellington for one month's availability. On May 16, 1943 she proceeded to Pago Pago and brought units of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines back to Auckland. Arriving at Wellington on June 3rd, her next departure for Guadalcanal was June 30th with 49 officers and 1,159 enlisted men of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines. Depth charges were dropped for a fifteen minute period on this trip by the escort and the ships made a series of emergency turns until the contact was lost. Returning to Auckland on July 15th the Liggett took aboard 79 officers and 1,643 men of the 2nd Battalion, 19th Marines and arrived at Guadalcanal on the 30th. On August 13th the Liggett, while on her 11th trip to Guadalcanal, was to undergo another air attack. At 2030 Condition Red was established and shore searchlights sweeping the sky, occasionally picked up a high-flying Japanese plane. Then came a terrific explosion. A fierce fire was seen, the flames rising high into the sky. The victim was the USS John Penn, sunk by an aerial torpedo while berthed in the anchorage off Lunga Point that had been occupied by the Liggett on the previous day. On the next trip to Guadalcanal, on September 3rd, two or three bombs exploded close off the Liggett's starboard bow. The Liggett arrived with troops again on the 5th of October from Wellington and on the 17th of October, 1943 from Vela Harbor. Then she returned to Vela Harbor and made preparation for landing Marines on Bougainville.

--23--

Table of Contents

Next Chapter (2)

Footnotes

1.

For complete list of vessels wholly or partially Coast Guard manned see

Appendix A, All but four of the 23 transports and destroyer transports in Task Force TARE had Coast Guardsmen aboard.

2.

Amphibious Tractors were first used at Tarawa.